Children who grow up with greener surroundings have up to 55% less risk of developing various mental disorders later in life. This is shown by a new study from Aarhus University, Denmark, emphasizing the need for designing green and healthy cities for the future.

More: Residential Green Space

Kristine Engemann, Carsten Bøcker Pedersen, Lars Arge, Constantinos Tsirogiannis, Preben Bo Mortensen, and Jens-Christian Svenning

PNAS March 12, 2019 116 (11) 5188-5193; first published February 25, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1807504116

Edited by Terry Hartig, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Susan T. Fiske January 14, 2019 (received for review May 2, 2018)

Significance

Growing up in urban environments is associated with risk of developing psychiatric disorders, but the underlying mechanisms are unknown. Green space can provide mental health benefits and possibly lower risk of psychiatric disorders. This nation-wide study covering >900,000 people shows that children who grew up with the lowest levels of green space had up to 55% higher risk of developing a psychiatric disorder independent from effects of other known risk factors. Stronger association between cumulated green space and risk during childhood constitutes evidence that prolonged presence of green space is important. Our findings affirm that integrating natural environments into urban planning is a promising approach to improve mental health and reduce the rising global burden of psychiatric disorders.

Abstract

Urban residence is associated with a higher risk of some psychiatric disorders, but the underlying drivers remain unknown. There is increasing evidence that the level of exposure to natural environments impacts mental health, but few large-scale epidemiological studies have assessed the general existence and importance of such associations. Here, we investigate the prospective association between green space and mental health in the Danish population. Green space presence was assessed at the individual level using high-resolution satellite data to calculate the normalized difference vegetation index within a 210 × 210 m square around each person’s place of residence (∼1 million people) from birth to the age of 10. We show that high levels of green space presence during childhood are associated with lower risk of a wide spectrum of psychiatric disorders later in life. Risk for subsequent mental illness for those who lived with the lowest level of green space during childhood was up to 55% higher across various disorders compared with those who lived with the highest level of green space. The association remained even after adjusting for urbanization, socioeconomic factors, parental history of mental illness, and parental age. Stronger association of cumulative green space presence during childhood compared with single-year green space presence suggests that presence throughout childhood is important. Our results show that green space during childhood is associated with better mental health, supporting efforts to better integrate natural environments into urban planning and childhood life.

Results

Relative risk, estimated as incidence rate ratios (IRR), was higher for persons living at the lowest NDVI compared with those living at the highest levels of NDVI for all psychiatric disorders, except intellectual disability (IRR: 1.04; 95% CI: 0.95 to 1.14) and schizoaffective disorder (IRR: 1.33; 95% CI: 0.98 to 1.82) (Fig. 1). Adjusting for urbanization, parents’ socioeconomic status, family history, parental age, municipal socioeconomic factors, and a combination of all five potential confounding factors only changed the risk estimates slightly, with no change to the overall association with NDVI, except for borderline type, anorexia, and bipolar disorder for which adjusting for all five factors made green space presence insignificant (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Population attributable risk estimates showed that the association between NDVI and psychiatric disorder risk was, in general, comparable in magnitude to that of family history and parental age, higher than urbanization, and slightly lower than parents’ socioeconomic status (SI Appendix, Table S1). Substance abuse disorders, specific personality disorder, borderline type, and intellectual disability risk were mostly associated with parents’ socioeconomic status, while mood disorder, single and recurrent depressive disorder, and neurotic, stress-related, and somatic disorder risk were mostly associated with NDVI, although the last has an association of similar strength as parents’ socioeconomic status.

Figure 1

The association between childhood green space presence and the relative risk of developing a psychiatric disorder later in life. Green space presence was measured as the mean NDVI within a 210 × 210 m square around place of residence (n = 943,027). Low values of NDVI indicate sparse vegetation, and high values indicate dense vegetation. Relative risk estimates are relative to the reference level (set to the highest decile) for NDVI fitted as numeric deciles in classes of 10. Estimates above the dashed line indicate higher risk of developing a given psychiatric disorder for children living at the lowest compared with the highest values of NDVI. Three additional models were fitted to adjust for the effect of urbanization, parental socioeconomic status (SES), and the combined effect of urbanization, parental and municipal socioeconomic factors, parental history of mental illness, and parental age at birth on risk estimates. All estimates were adjusted for age, year of birth, and gender and plotted with 95% CIs.

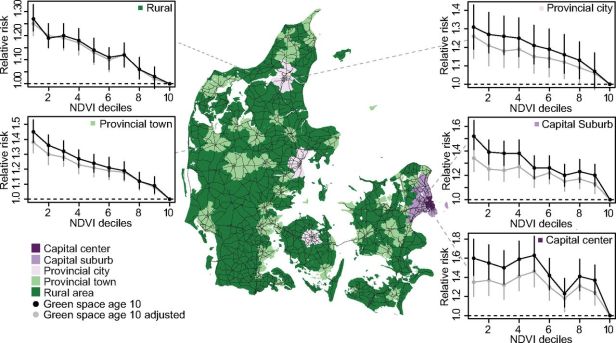

The relative risk of developing any psychiatric disorder was related to NDVI in a dose–response relationship across urbanization levels, with risk declining incrementally with higher doses of green space, although nonmonotonically for the capital center region (Fig. 2). Mean NDVI was lowest for the capital center area, but the range of NDVI values was represented across each urbanization category (SI Appendix, Table S2). The strongest association between relative risk and the lowest decile of green space presence was for the capital center region (NDVI decile 1; IRR1: 1.60; 95% CI1: 1.42 to 1.80) and the weakest association was for rural areas (IRR1: 1.27; 95% CI1: 1.22 to 1.33). Although a Cox regression model with an interaction term showed that the association with NDVI varied significantly across the different degrees of urbanization (P = 0.001, chisq = 97.8, df = 36), the general pattern of lower NDVI being associated with higher risk was similar within each degree of urbanization. Adjusting for urbanization and parents’ socioeconomic status only slightly lowered estimates.

Figure 2

The association between relative risk of developing any psychiatric disorder and childhood green space presence across urbanization levels. Data were split between each of the five urbanization classes (Capital center n = 56 650, Capital suburb n = 124,193, Provincial city n = 90,648, Provincial town n = 265,570, and Rural n = 376,525). NDVI was recalculated as deciles, and separate models, shown in black, were fitted within each urbanization class to determine the shape of the association between green space and mental health. Integer values on the xaxis refer to decile ranges, i.e., 1 corresponds to decile 0 to 10%. An additional model, shown in grey, was fitted for each urbanization class to adjust for urbanization and parents’ socioeconomic status. Estimates of relative risk from all five models were adjusted for year of birth and gender and plotted with 95% CIs within each degree of urbanization.

We found no consistent sign of green space presence being associated with any particularly sensitive age across all disorders (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Alcohol abuse, specific personality disorders, and borderline type diverged from the general pattern, with a tendency toward stronger protective associations occurring at age 3 y to 4 y based on the nonoverlapping confidence intervals between individual estimates. We compared the association with cumulated green space presence by fitting models with deciles of mean NDVI at the 10th birthday and as cumulated NDVI from birth to the 10th birthday. Mean and cumulated NDVI were both associated with risk in a dose–response relationship, with children living at the lowest green space presence having the highest risk of developing a psychiatric disorder (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Risk estimates were generally higher for cumulated green space presence than presence measured at age 10 y, again suggesting an accumulating dose–response relationship. About half of all cases across all disorders were diagnosed in adulthood (age >19 y) (SI Appendix, Table S3). Splitting data between persons diagnosed in adolescence (age 13 y to 19 y) and adulthood showed a stronger association between risk of any psychiatric disorder and green space for the former (IRR1: 1.64; 95% CI1: 1.58 to 1.70) than the latter age category (IRR1: 1.43; 95% CI1: 1.35 to 1.52), with no change in the direction of the association (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Associations mostly did not differ between the two age groups for individual disorders, with the exception of substance and cannabis abuse. Both substance and cannabis abuse showed stronger associations between risk and green space for persons diagnosed in adolescence; however, cannabis abuse diagnosed in adulthood was statistically insignificant due to low sample size in the first half of the sampling period. We found no strong difference in the association between risk and green space measured at 210 × 210 m, 330 × 330 m, 570 × 570 m, or 930 × 930 m presence zones (SI Appendix, Table S4). For both the age sensitivity and cumulated green space analysis, adjusting for urbanization and parents’ socioeconomic status only slightly lowered risk estimates.

More: PNAS Link

63. The Effect of Traveling and Colors on Personal Health (In Work)